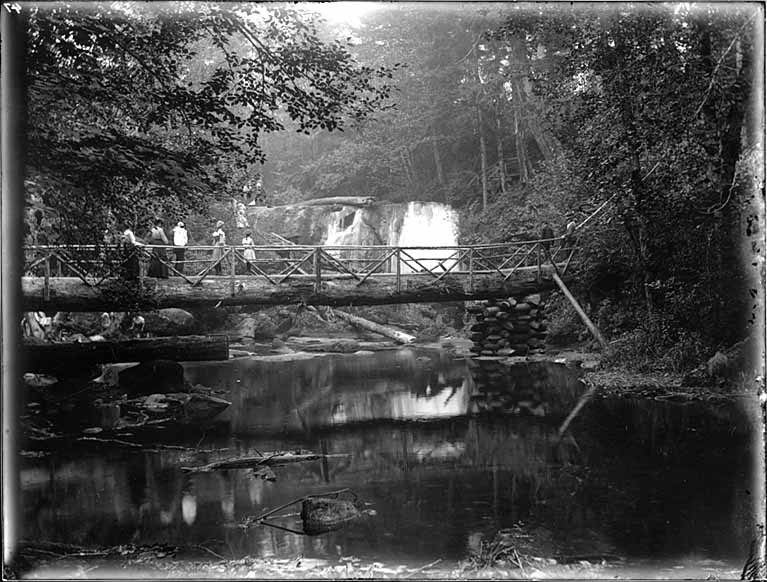

The word Xwótqwem describes a specific place: the lower falls on Whatcom Creek, where water once plunged directly into Bellingham Bay. Galloway and Richardson note that this waterfall “probably plunged right into the ocean where now there is landfill for approximately 0.25 miles.” The creek drains Lake Whatcom into the bay, and the falls once marked the transition from freshwater to saltwater, a place where salmon gathered and where both Nooksack and Lummi peoples camped to harvest seafood.

The falls still exist, between what are now Prospect Street and W. Holly Street in Bellingham. But the landscape that gave the word its meaning has been fundamentally altered. Landfill has pushed the shoreline a quarter mile from where it once was. The sound that Xwótqwem describes (water crashing fast and hard into saltwater) is gone.

How the name traveled

The name moved from Indigenous place-name to settler settlement to county through a sequence of colonial acts spanning just over two years.

Before 1852

The word Xwótqwem / QwotQwem described the waterfall, the creek, and the seasonal camp at the creek mouth. Lummi and Nooksack peoples used this site for fishing and gathering. The word belonged to the place and the place belonged to the peoples who named it.

December 1852

Captain Henry Roeder (1824 to 1902), a German-born Ohioan, and Russell V. Peabody arrived on Bellingham Bay from San Francisco seeking a waterfall to power a sawmill. In Olympia, they had met Lummi Chief Chow’it’sut (d. 1861), who directed them to the falls at “What-Coom” and gave them permission to settle and use the site. Chow’it’sut also promised to send Lummi men to help raise the mill.

This was an act of diplomacy and generosity. It became the vector through which the name was extracted from its Indigenous context and applied to colonial geography. The settlement that grew around the sawmill was called “Whatcom,” the first permanent American town on Bellingham Bay.

March 1, 1854

Geographer George Gibbs, working on the Pacific Railroad survey, documented “Whatcom Lake” in his report, confirming the name was already in common settler usage for the lake, creek, and settlement. Gibbs recorded approximately 310 Indigenous place names in the region, including roughly 55 Nooksack names. His materials are foundational to all later scholarship on the region’s Indigenous toponyms.

March 9, 1854

The first session of the Washington Territorial Legislature, meeting in the second story of a dry goods store in Olympia, created Whatcom County from Island County. It was one of eight new counties established during that inaugural session. No specific legislator has been identified as proposing the name; it was adopted from the existing settlement name.

No evidence exists of any consultation with Lummi, Nooksack, or other Indigenous peoples regarding the naming.

January 22, 1855

The Treaty of Point Elliott was signed, nearly a year after the county received its name. This is the treaty that formally ceded Indigenous lands in the region. Chief Chow’it’sut signed it as “head chief” of the Lummi. The county had already been carved from his people’s territory and named with his people’s word before the legal mechanism for dispossession was even in place.

The settler record

Roeder’s daughter, Lottie Roeder Roth, later wrote the foundational History of Whatcom County (Pioneer Historical Publishing Co., 1926, 2 volumes), which became a primary local source but told the story entirely from the settler perspective. The Center for Pacific Northwest Studies at Western Washington University published an index to this work in 1979.

Today the word “Whatcom” is everywhere: county, creek, falls, lake, college, media outlets, road signs, business names. All derived from a Coast Salish word. Most residents are unaware of the connection. The name that was taken without consultation has become so naturalized that its Indigenous origin is essentially invisible.

This is not just a local story. It is part of a national pattern of toponymic extraction, the colonial practice of absorbing Indigenous place names while severing the connection to Indigenous peoples and languages. And the translated meaning, “noisy water,” has been further extracted as a branding device by non-Indigenous organizations throughout the county.

Continue reading: Who Profits from “Noisy Water”, on how the translated meaning became a brand.